Hello! Welcome to Nosh Box, a lunchtime-ish food newsletter that tries not to make anyone feel crabby.

Read yesterday’s dispatch: Why we can't rely on carbon-offset farming to save us

One of Turkey’s most popular apps — bigger than Tinder — is called Faladdin. It uses AI to replicate the centuries-old Turkish tradition of reading fortunes from coffee grounds, known as fal.

Users upload photos of their coffee cups plus basic demographic data, and within 15 minutes, the app’s AI platform produces a free reading based on more than 6,000 fortunes from 30+ contributors. It’s phenomenally successful and took in over $5 million in revenue last year, primarily from ads. But what does this mean for the future of Turkish coffeehouse fal culture?

At Rest of World, Kaya Genç brings us the story of Faladdin; of Sertaç Taşdelen, the entrepreneur and model who created the app; and of the often uneasy coexistence between an app and the real-life phenomenon it’s designed to disrupt:

Human unpredictability presents Taşdelen with opportunities and challenges. He has noticed that [real-life] oracles often demand more time and money for providing a service similar to his. He also says that most millennials prefer written communication to in-person encounters and want to avoid potential awkwardness by receiving fal via text. At the same time, Taşdelen says, Turks often treat oracles as friends and rely on them for “an irreplaceable human connection,” which algorithms obviously can’t provide. But he insists that users shouldn’t have to choose between one or the other: after all, somebody can use a meditation app in the morning and still go to therapy at night.

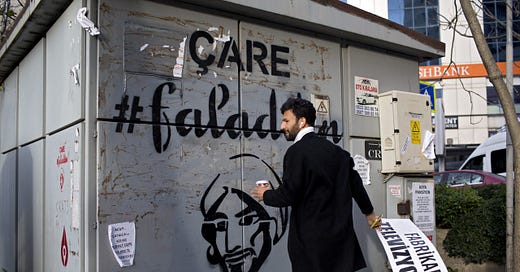

Sertaç Taşdelen, the creator of Faladdin. Photo by Danielle Villasana/Redux for Rest of World

The first app Taşdelen created was called Binnaz, named for his mother, a well-respected fortune teller and pharmacist in Ankara. Through Binnaz, over 1,000 actual fortune tellers produce readings for users who pay to upload photos of their coffee cups. But last year, Taşdelen decided to scale up. Faladdin, which is free and relies on ad revenue, now has more than 5 million active monthly users, well beyond the scope of an app like Binnaz.

Of course, people who use Faladdin are aware that there’s not a human on the other end of what’s otherwise an individualized, traditional, and only quasi-legal practice. And that seems to be just fine.

Faladdin’s business model depends in no small part on irrational belief. It dances along the disappearing border between the unknown algorithms of new technologies and ancient prophetic traditions, teasing the possibility that it might just know something we don’t. Is suspending disbelief in technology any different than doing the same with religion? We give Faladdin our consent and data so it can predict our desires and anticipate our next move, the same way a Netflix recommendation or a Google search autofill might. This can be disconcerting, but many people feel otherwise. As Faladdin’s success attests, we clearly take some kind of comfort in being seen and in having choices made for us, without being forced to deal with another person’s judgment.

Here’s the article if you want to read more.

(h/t Caitlin Dewey’s fantastic Links I Would Gchat You If We Were Quarantined newsletter)

An important essay to read this weekend:

“Black Communities Have Always Used Food as Protest,” Amethyst Ganaway writes at Food & Wine.

She traces the history of Black people using food as a way to preserve their culture and resist oppression: From traditional African religions, to enslaved Africans braiding seeds into their hair before being forced across the Atlantic, to gardens maintained by enslaved people on plantations, to the often-invisible work of feeding activists during the Civil Rights Movement, to the Black Panther Party’s food aid programs, to the reclamation of “soul food” as Black culture, and more.

It’s impossible to put the thousands of years of Black history, revolution, and food into one story, but as we see another generation take to the streets to demand justice for Black lives that have been lost, and for retribution for injustices inflicted over hundreds of years, food finds its way into the resistance again.

While food companies, upscale restaurant groups, and brands post their stances on protesting and social injustices on the internet, Black communities keep up the work of feeding their communities and supporting protests. Black lives lead the vanguard toward equality and revolution as they have done so many times before. We are demanding, not asking, for “Land, Bread, Housing, Education, Clothing, Justice And Peace.”