A brief inquiry into the names of various meats

Issue 197: Yes, boneless wings aren't truly wings. But Impossible meat isn't biologically meat, either. So do we need to rename them?

Hello! Welcome to Nosh Box, a lunchtime-ish food solutions newsletter. On Mondays, I send a reading guide of food system fix news, and on Thursdays, I dig deeper with an original essay you can only get here.

Check out Monday’s dispatch — Maybe all owners should "loot" their own stores to donate to the community. Plus — meatpacking giants are (maybe) exaggerating shortages as a ploy to protect profits and exploit workers. The power of co-op groceries. Historical ice cream flavors.

It’s rare that a livestream of a city council meeting goes viral, but this week’s meeting in Lincoln, Nebraska, has amassed more views than there are people in the city of Lincoln, as the New York Times helpfully calculated.

Why? Well, Ander Christensen, a 27-year-old chemical engineer, has identified a problem that’s gotten out of hand, so he decided to embody democracy in action to fix it.

“I propose that we, as a city, remove the name ‘boneless wings’ from our menus and from our hearts.”

Again: why?

“Number one: Nothing about boneless chicken wings actually comes from the wing of a chicken. We would be disgusted if a butcher was mislabeling their cuts of meats, but then we go around pretending as though the breast of a chicken is its wing?

Number two: Boneless chicken wings are just chicken tenders, which are already boneless. I don’t go to order boneless tacos. I don’t go and order boneless club sandwiches. I don’t ask for boneless auto repair. It’s just what’s expected.

Number three: We need to raise our children better. Our children are raised being afraid of having bones attached to their meat. That’s where meat comes from. It grows on bones. We need to teach them that the wing of a chicken is from a chicken, and it’s delicious.

I propose that we rename boneless wings in the city of Lincoln. We can call them ‘Buffalo-style chicken tenders.’ We can call them ‘wet tenders.’ We can call them ‘saucy nugs,’ or ‘trash.’ We can take these steps and show the country where we stand and that we understand that we’ve been living a lie for far too long, and we know it, because we feel it in our bones.”

On the one hand, it’s Parks and Rec-level satire of the self-seriousness afforded to trivial matters in local government. But on the other hand, I think it raises a genuinely interesting question: Does it matter what we call our meat?

The debate about which foods can even be called “meat” in the first place was preceded by another fiery conflict, still raging, about the identity of nut- and plant-based milks.

“An almond doesn’t lactate,” former FDA head Scott Gottlieb declared a few years ago, announcing his intention for the agency to consider a ban on plant-based milks calling themselves “milk.” Technically, per the FDA, “Milk is the lacteal secretion, practically free from colostrum, obtained by the complete milking of one or more healthy cows.” But, of course, the FDA doesn’t currently enforce this definition very strongly — evidenced not only by the fact that nut milk manufacturers are actively using the term “milk,” but also because the standards seem to suggest goat’s and sheep’s milks wouldn’t qualify as “milk” either.

So for years now, the dairy industry has been lobbying for the FDA to kick up enforcement of these standards and effectively ban plant-based milk producers from using the word “milk.” (Nothing major came of Gottlieb’s announcement, by the way.) Their argument is essentially that it deceives customers into thinking vegan milk has as good a nutritional profile as dairy milk — which they argue it does not — and that it’s co-opting milk’s good name.

Just take the lawsuit filed against vegan butter producer Miyoko’s Kitchen in 2018, which alleged the cashew-based butter “basks in dairy’s ‘halo’ by using familiar terms to invoke positive traits, including the significant levels of various nutrients typically associated with real dairy foods.” (The lawsuit was dismissed last year.)

We see almost the same playbook being used in the meat world, as plant-based brands like Beyond and Impossible gain traction, and research continues on cultivating meat in a lab from animal cells. The USDA and FDA started a lengthy rulemaking process last month on what to call cell-cultivated meat, but since well before that, beefy vested interests have been saying Beyond and Impossible have no business officially being meat.

(no bones about it. Photo from NYTimes)

In 2018, Missouri — which, notably, is where Beyond Meat’s plant is located — passed a law banning meat alternatives from being called “meat.” As Mike Deering, the executive vice president of the Missouri Cattlemen’s Association, put it to the New York Times:

“Making sure that consumers knew what they were buying was the whole intent. You cannot market a station wagon as a Porsche.”

The idea being that if only customers could be sure that “meat” or “milk” exclusively referred to animal-based products, they wouldn’t “accidentally” buy the plant-based stuff and would spend more money on beef and dairy. I think this takes a pretty dim view of the consumer by assuming they aren’t actually smart enough to know what they’re buying — not that they’re simply making an informed choice and your product doesn’t cut it. (As Julie Guthman tells us, when people don’t do something you think they should do, the reason is often not because they don’t know better!)

And to Mike Deering’s point: Who gets confused between a station wagon and a Porsche? People who buy each type of car know very much what they’re getting into; they’re perfectly aware that the two cars have different insides and different purposes. If consumers recognize the environmental benefits of plant-based meat substitutes (even if they’re not exactly healthier), preventing companies from using the word “meat” is not going to make livestock production any more sustainable.

And as I’ve talked about here before, it’s often desirable to retain terms that carry cultural meanings beyond their dictionary definitions. When cookbook authors anglicize the names of traditional recipes — bibimbap becomes a “Korean vegetable rice bowl” or chana masala is branded as an innovative “spiced chickpea stew with coconut and turmeric” — whiteness is reinforced as “neutral” or the norm. In a previous Nosh Box, I included an article from Bettina Makalintal at Vice that pointed to Priya Krishna’s recipe names, such as “spinach and feta cooked like saag paneer,” as a way to honor a dish’s roots while leaving room for creativity. It’s specific and denotes both the existence of the classic preparation and the way the current iteration departs from it — much like “oat milk,” which tells us that the product is akin to dairy milk in cultural function but explicitly not the same. It’s about descriptive accuracy and cultural meaning.

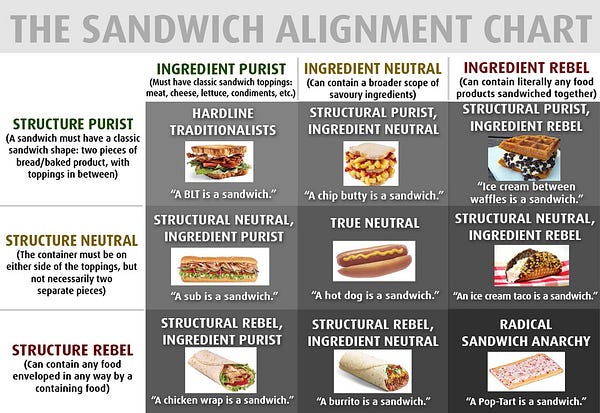

This is why, when it comes to food categorization, I personally tend to take a more functional viewpoint, rather than the essentializing one the beef and dairy industries seem to adopt. If you use oat milk the same way you’d use dairy milk, fine. It can be a milk. Is a hot dog a substantive filling between holdable bread? Yep, it’s a sandwich. (Full disclosure: I struggle with the Pop-Tart being ravioli, though, because outside of some sort of deranged social experiment, a Pop-Tart would never be served in marinara sauce as a functional replacement for ravioli. However, I could be convinced that a Pop-Tart is a sweet calzone. Roast me in the comments below.)

So. Back to the boneless chicken wings subject. I think, for this reason — and this might be controversial! — I don’t have a huge problem with “boneless wings.” The food serves a similar functional purpose, within our modern cultural context, to chicken wings. And by labelling them “boneless,” it’s clear that they are both akin to bone-in wings but depart from bone-in wings in a very specific way.

And, given the traditional placement of chicken tenders/fingers/nuggets on kids’ menus, which imbues them with a sense of juvenility that’s reflected back onto an adult eater (stay tuned for my master’s thesis on this; get pumped!) I don’t think rebranding boneless wings as “wet tenders” or any other existent chicken word would fly with the stereotypically hyper-masculine sports bar crowd. And many of these terms already refer to existent foods with different structures and functions than a boneless wing. So we’d just run into the same problem.

That said, the part I find most appealing (and difficult to reconcile) about Christensen’s speech is his third point, about the necessity of making it clear, especially to kids, that wings are biologically attached to bones, which come from an animal. Even if we continue somewhat erroneously calling a breaded chicken breast piece a “boneless wing” — with the explanation that it’s not truly a wing but so called because it serves a similar social function to an actual wing — I think society in general would benefit from a better understanding of where our meat comes from and how it lands on our plate.

It seems to me that if one were genuinely worried about people being confused by the animalistic provenance of their meat, calling beef “beef” to obscure the fact that it’s from a cow would be a bigger fish to fry, so to speak. We have all sorts of euphemisms for different meats — pork, veal, mutton, venison — which largely stem from class divisions following the Norman conquest of England in the 11th century but today have come to represent a functional distinction between, for example, the edible quality of “beef” and inedible quality of “cow.” (So I’m not convinced this is a problem that needs fixing either.) Chicken, as it happens, is what we call both the living and culinary animal, which helps on the understanding-biological-realities front and maybe makes “boneless wing” a little more palatable.

I don’t think replacing “boneless wing” with another existing term (“tender,” “nugget,” “breaded chicken breast chunk”) would teach people more about poultry supply chains, which is what we actually need to do. Having conversations with kids about how the food system works — incorporating food studies into school curricula — seems like it would be much more effective!

There are so many different facets to explore here in terms of our linguistic interactions with our food — I don’t think I’ve even fully explored the boneless wing debate — and language and meaning are topics I’ll come back to in future issues of Nosh Box. But for now, what do you think? Comment below!

I'm looking forward to the Milk industry going after Phillips' 'Milk of Magnesia' and Shakespeare's 'milk of human kindness.' And how about that Biblical phrase, 'a land flowing with milk and honey!' Milkweed and the Milkweed butterfly!

I loved this. Hurray for local governments, and I can't wait for your thesis!